Established in 1962, Mira Godard Gallery is one of Canada's premier commercial art galleries featuring paintings, sculpture and works on paper including original prints and photographs. With three floors of exhibition space and viewing room, Mira Godard Gallery focuses on contemporary Canadian and International art. We are proud to represent major artists who have won distinction here and abroad. Many of the works which have been shown at the Mira Godard Gallery have become part of the permanent collections of public galleries, museums and corporations.

For over half a century the Mira Godard Gallery label on the back of a work of art represents the highest standard of quality and provenance - provenance which is cited by museums and Canadian auction houses. Collectors, museums and Canadian auction houses know that Mira Godard Gallery has, for almost sixty years, represented Canada's most important artists and has had direct and personal working relationships with those artists. The David Milne Estate, Alex Colville, Christopher Pratt, Jean McEwen and a number of other major artists have chosen their best works to be sent to Mira Godard Gallery.

For five decades, Mira Godard Gallery has worked directly and discreetly with corporate and private collectors in building collections, providing appraisals and buying and consigning works for re-sale.

Mira Godard arrived in Montreal in 1950 after having studied art, physics and math at the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne in Paris. She [applied her broad and vigorous intellect] to her first major career move, the purchase in 1962 of the innovative Agnes Lefort Gallery in Montreal. She then relocated to Toronto and opened her eponymous Yorkville Gallery. At the end of the 1970s she blazed a trail west to Calgary - a place few gallerists dared to venture at the time.

Godard was known for her passionate arts advocacy. Her association with the prestigious New York and London based Marlborough Galleries and her hosting of an important 1965 show of late- Picasso works testified to her desire to make ties outside the domestic scene. Meanwhile, her Toronto Gallery amassed some of the biggest names in Canadian art: Alex Colville, Christopher and Mary Pratt, Takao Tanabe and the estates of David Milne and Lawren Harris. She was a founding member and the first president of the Art Dealers Association of Canada.

Mira Godard: A Pioneer Passes, David Balzer, Canadian Art, 2010

-

OUR HISTORY

Mira Godard Gallery has been a leader in the Canadian art world through seven decades, celebrating its sixtieth anniversary in 2022. Long a familiar Toronto institution, the gallery’s roots are in Montreal, where it was founded as Galerie Agnès Lefort in 1950. In 1961, Mira Godard bought the gallery from Agnès Lefort, taking sole direction of the gallery in 1962. For almost fifty years Mira Godard was at the forefront of art in Canada at the helm of her eponymous institution. On her passing in 2010, Godard was described by Canadian Art magazine as a “true titan,” with editor David Balzer noting her importance to both Canadian and International art over her storied career.

-

Agnès Lefort — Essay by Dr. Lora Senechal Carney

Not long after Agnès Lefort opened her very unusual gallery in Montreal, she installed in front of it a larger-than-life abstract sculpture of a family by the young artist Robert Roussil. An innocent enough gesture, but since the figures were nude, the city said Lefort needed authorization from the chief of police to have it in public. She was ordered to remove it. She refused in the name of artistic freedom, and then learned she had to appear in municipal court to face the charge of public indecency.

Two days later she reported hearing a suspicious noise and looked through the window, where she saw a young man taking a stick to the sculpture. She caught up with him a few blocks away. “When I asked him why he did that, he answered that the statue ought to be destroyed.” She chose not to lay criminal charges for the damage, but in the press, the incident added a colourful element to an already juicy story.

With many people rising to the debate, for and against, Lefort eventually agreed to pay a small fine and remove the sculpture rather than risk ending her new enterprise. The story and all the publicity surrounding it made quite an impression in the early days of the Galérie Agnès Lefort.

We get a clearer picture of this gallery and the artist-curator behind it from two eminent Quebec art historians. In the mid-nineties, Helène Sicotte researched and wrote about the gallery and its place in the Montreal art scene, and more recently Esther Trépanier has begun the exploration of Lefort’s earlier life and art. It is all part of a larger effort to restore to their proper place the women whose contributions have long been overlooked in the history of art in Quebec.

Lefort’s first professional work was in advertising and illustration but even as she pursued that career, she kept up her childhood enthusiasm for art through evening classes. Eventually she began to do some teaching at an English language girls’ school and in her own studio. She showed her paintings regularly at both the Spring Exhibition of the Montreal Museum of Fine Art and the Royal Canadian Academy (and the fact that she showed at the Academy reveals that while her very accomplished portraits and her other work may have been modern in approach, they were definitely not avant-garde). She had her first solo show at Eaton’s Fine Art Galleries in 1935, in the period when Montreal’s larger department stores did such things.

Lefort continued to earn her living in advertising and illustration through the forties. During World War Two she wrote scripts in support of the war effort for French-language radio for distribution in Canada and abroad (and she carried on afterwards with peacetime Radio Canada broadcasts on art). Painting remained central to her life through all of this, and she was well enough known and respected to be chosen after the war to participate with six other Montreal painters in Femina, the first exhibition ever devoted strictly to Quebec women artists, and also in Canadian Women Artists, shown in New York and then Montreal and Toronto.

What caused her painting to take a more modernist turn at the end of the forties? One possible factor was the change in atmosphere in Montreal. Conservative work still prevailed at the galleries but the city now had artists who rebelled against it, including the now famous Automatistes led by Paul-Émile Borduas. Montreal also had a lively critical tradition that far exceeded anything in other Canadian cities. Public interest was growing too: the Ontario critic Donald Buchanan remarked already in 1945 that in Montreal, which was “once the citadel of derivative tastes in art, a long retarded but now absolutely genuine enthusiasm for modern painting has developed,” especially among the professional classes. And, as soon as the war ended, there again began a flow of artists and ideas between Montreal and Paris, and this certainly helped to animate the scene. Lefort herself went to Paris in 1948, made many contacts in the art world, and studied in the Académie d’André Lhote, where she developed a post-cubist form of painting that seemed to satisfy her. Hélène Sicotte tells us that Lefort may also have thought of opening a gallery in advance of her trip to France, and was exploring the possibilities there.

She presented her new paintings the following year in Montreal in a show that included landscapes, portraits, still lifes, nudes, and even sporting pictures in her new abstracted style. The critic Rolland Boulanger noted that she had joined the best tradition of French constructivist painting. Charles Doyon, an important art writer of the time, published a review that was encouraging in both its attentiveness and its very substantial length. Unfortunately, however, her dealer didn’t find the work salable.

What to do with a public that mostly disliked anything new in spite of the changes in the air, and a gallery system that catered to that public’s conservative impulses? If you were Agnès Lefort, you didn’t get a job in the familiar world of advertising, which surely would have been safer: you opened the city’s first gallery for art vivant, living art. In October 1950, then, the bilingual, bicultural Galérie Agnès Lefort appeared on Sherbrooke Street near McGill. She explained a decade later that “I went into this field as one who dives into water for the first time. Luckily I was able to sell a number of my own paintings in the first year, and gradually the gallery began to make money.” Within two years, a prominent critic found the Galérie Agnès Lefort to be “one of the main art centres of the city.”

After the first few years she moved to 1504 Sherbrooke, just west of the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal’s wealthy Golden Square Mile. She lived at the back of the new space for a while to make ends meet. She also continued to teach, including in the Laurentians in the summer program at the Centre d’Art de Ste Adèle, which she had helped to establish in 1948. “I told our visitors about the modern art,” she explained later to Colin Haworth, one of the artists she exhibited. “I told them about Borduas, Riopelle and the others. I showed them the works and tried to explain. What came over me suddenly one day was the fact that these other Canadians, outside the mainstream of art (Americans too vacationed at Ste Adèle), actually wanted to know what it was all about.” And throughout her gallery career she would focus on educating those who came through the doors, persuading them to put aside prejudices. "If you came here in the same state of mind as you bring to music, not expecting something you recognize but something which will charm you, you would enjoy it. After all, every famous painting is built on form and colour in space.” When the spectator as “co-creator” is receptive as to music, she said, modern art will have a larger purpose in the new era: it will “save thought” from the flood of readymade ideas that was saturating minds in the age of television and other modern media.

These convictions were no doubt what made her such a persuasive dealer. She also turned out to be a good businesswoman. She kept her prices low for the young artists she exhibited in the interests both of getting them established and of building a base of young collectors. She made no exclusive contracts with the artists. She allowed buyers who had enthusiasm but little money to pay in instalments. She sold not only to private clients, who after the first years were mostly but not exclusively francophone, but also occasionally to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the National Gallery of Canada, and the Musée du Province de Québec (now MNBAQ). Toward the end of the fifties, Hélène Sicotte reports, another category of client came along: companies that wanted to start their own art collections.

In her eleven years as a galeriste she was especially loved by young quebecois artists, many of whom had their first solo shows the Galèrie Agnès Lefort. They are “at home in the place,” said the artist Michael Forster, “and adore the fact that they’re dealing with a human being, not simply an efficient salesman.” Marcelle Ferron and Jean McEwen were among quite a few who had their first shows with Lefort and who later became well-known. She showed anglo-Canadians too, and international artists, especially French, but the Canadians got preference. “Just list the seventy or eighty names of the painters and sculptors who can boast of their shows at Galerie Lefort, the original shop or the later address on Sherbrooke near the Museum. It would read like several pages out of a who’s who of contemporary Canadian art,” wrote Colin Haworth.

Among her collective shows she included, her first year, a Salon de la Jeune Peinture Canadienne, the word jeune referring to a constantly creative approach rather than age, as Geneviève Lafleur explains in her study of women and postwar Montreal galleries. It was an eclectic grouping of “artists who don’t group themselves together,” Lefort said. Over the years she showed not only paintings and sculpture, but also collages and other media, especially prints. While she did not show Indigenous art, she had something like a twenty-first century understanding of it: “I have a profound admiration for the splendid art of the Indians of Vancouver, but we have taken nothing from the Indian but his lands and his liberty.”[1]

“Riopelle, Borduas, Roberts, Pellan, Ghitta Caiserman-Roth, Tonnancour and Cosgrove formed her avant-garde,” said Denys Matte, another artist who exhibited with her, and Lefort’s credibility (and many of her sales) may have come from this fact, although her welcome to young artists particularly endeared her to the community.

Increasingly, as time passed Lefort favoured abstracted and nonobjective work. In a 1955 article in the magazine Points de vue she wrote that “one must imagine, must create correspondences with another world, to get beyond the quotidian” [my translation], and this is the task of art. Borduas was her star. In 1954 she presented his work in the exhibition En route!, a show now understood to have definitively established non-figurative work in Montreal. She showed him twice more, and even after he had moved on she remained his “chère amie” in their correspondence.

She generated substantial publicity for her shows and there was a steady stream of invitations, ads, press releases and press conferences, and receptions. This is unsurprising for someone with an earlier career in advertising, but it also gives a clear sense of her devotion to the gallery’s project. In that respect, and more generally in her exhibitions and her endless persuasive conversations with gallery visitors, Lefort certainly contributed to the growth of a new public in Montreal.

It is interesting now to imagine this highly cultivated, well read, bilingual québécoise in her first acquaintance with the young multilingual engineer from Eastern Europe who walked into her gallery and eventually bought it. They must have been fascinating to each other.

[1] Lefort, “La peinture canadienne d’expression française,” Points de Vue 1, no. 2 (October 1955): 20.

-

About Mira Godard Gallery — Essay by Ray Cronin

The Mira Godard Gallery has been a mainstay of the Canadian art world for six decades, and the gallery will celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of Mira Godard’s vision for Canadian art in 2022. On her passing in 2010, Godard was described by Canadian Art Magazine as a “true titan”, noting her importance to both Canadian and International art over her storied career. Long-time friend and exhibitor Christopher Pratt, summed up her accomplishments succinctly: “She changed and upgraded the understanding of ‘professional’ in the visual arts in Canada.”

Born in Bucharest, Romania, Godard emigrated to Canada in 1950 after studies in art and science at the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne in Paris. She continued her studies in Montréal, earning degrees in science and business administration. In 1961 she was working as an engineer in the aviation industry in Montréal. Feeling at an impasse in her life, she visited Galerie Agnès Lefort, “just to take my mind off it, just for a diversion.” As she further recalled to Sandra Gwyn for a 1977 article in Saturday Night Magazine, that diversion would change her life. “I went in to buy a print. I came out owning the gallery.”

While the purchase was finalized in the summer of 1961, Lefort stayed on at the gallery for several months to ease the transition to the new ownership. By early 1962, Godard was on her own. When acquired by Godard, Galerie Agnès Lefort was already a famed Montréal institution. Godard would follow Lefort’s lead, and build on her remarkable accomplishments.

Agnès Lefort (1891-1973) opened her gallery in 1950, and quickly established herself as the leading commercial gallery dedicated to contemporary Québec, Canadian, and French art. Artists whom she exhibited make up a who’s who of Montréal (and Canadian) art history: Alfred Pellan, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Fernande Leduc, Patterson Ewen, Takao Tanabe, Jean McEwen, Betty Goodwin, Rita Letendre, and Paul-Émile Borduas, among many. She was committed to promoting the work of contemporary artists in her city, and in building a market for advanced modernist art from Québec, the rest of Canada, and Europe. She was a passionate advocate for advanced art, and argued throughout her career for such art to be taken seriously: “How can we pretend to understand art if we don’t feel it, if we don’t let ourselves be affected by what we have seen? The receptiveness we bring to listening to a concert should not be less for the contemplation of a work of art,”[1] she wrote in 1951.

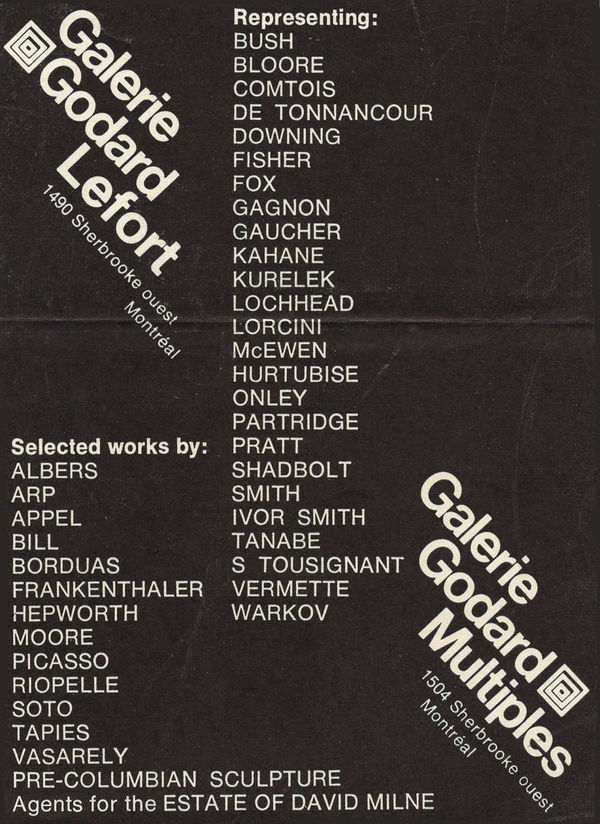

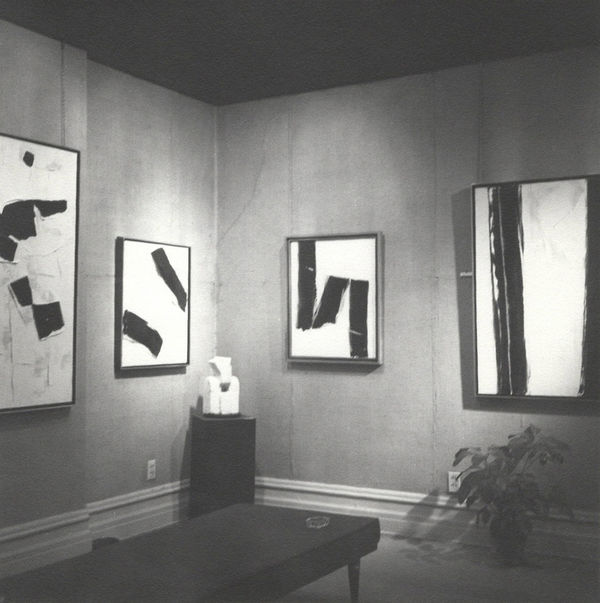

Mira Godard continued that legacy, and added to it an increased focus on art from across Canada. That year the gallery mounted fifteen exhibitions, including solo shows by artists (and estates) that are represented by Mira Godard Gallery to this day—Takao Tanabe and Jean McEwen. 1962 saw Godard set a pattern she would follow throughout her career: an ambitious slate of exhibitions, mixing up group shows with solos, emerging artists with established figures, international artists with artists from Canada, and, while concentrating on painting, also exhibiting a range of genres, including drawings, prints and small sculptures. In 1962 alone, four exhibitions featured group exhibitions of multiples or drawings—artworks that were more affordable and offered an entry point for emerging collectors—while the season was rounded out by group shows and solo painting exhibitions by prominent Canadian and International artists. Striking that balance has been a feature of Mira Godard Gallery ever since.

In 1963 Mira Godard surprised the Canadian art world by mounting the first solo exhibition by Arthur Lismer. While there had been museum exhibitions of his work, the renowned artist had never had a one-man show in a commercial gallery. When asked by the media why he’d never had his own exhibition, his answer was revealing of the then-state of the arts in Canada: “Because no one ever asked me,”[2] he said.

Godard’s ambitious programming continued into 1964, when she mounted a retrospective exhibition of the work of a mainstay of Galerie Agnès Lefort, Paul-Émile Borduas, who had died in 1960. Godard’s intention of bringing internationally acclaimed art to Montréal, and Canadian, collectors, mirrored the efforts made by the gallery’s namesake. Both woman cultivated strong relationships with the Parisian art world, and Godard made it a point of building relationships in New York. Her efforts bore fruit in 1966 with her ground-breaking exhibition The New York Scene, which featured several prominent New York-based artists, including Louise Nevelson, Anthony Caro, Jules Olitsky, Kenneth Noland, and Helen Frankenthaler.

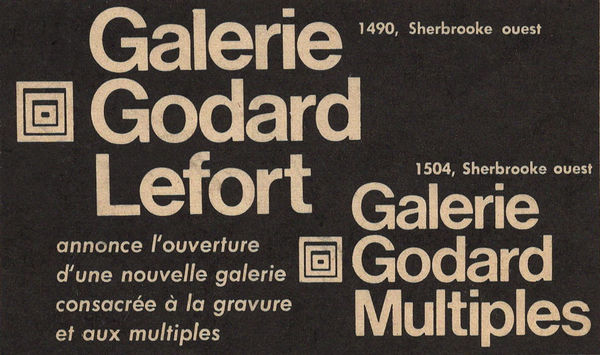

From 1962 Godard had retained the Galerie Agnès Lefort name. In 1967, however, she unveiled her new season under the Galerie Godard-Lefort banner. The first show of 1967 left no doubt of her continuing ambition: a solo show by the famous American abstract painter Josef Albers. In 1968 she mounted From Eugène Delcroix to Pablo Picasso, an exhibition of European masterworks, followed by 1969’s solo exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso. Godard’s programming was unmatched by any commercial gallery in Canada. Indeed, few public galleries, and certainly none in Montréal, were as ambitious.[3]

By 1968 the gallery had outgrown its original location, and Godard moved a few doors down Sherbrooke Street to a larger space. The new gallery was renovated according to designs by Montréal architect Joseph Baker, who would also design the gallery’s eventual location in Toronto’s Yorkville neighbourhood. One of the early shows in the new space was the first solo exhibition by rising star Jack Bush.

As her business continued to grow, so too did Godard’s position in the Canadian art world. In 1967 she was a founder of the Professional Art Dealer’s Association of Canada. She was elected its first president, a position she held for three years. She also served a term on an advisory committee that oversaw the government of Canada’s new ‘percent for art’ program in public buildings throughout the late 1960s.

In 1971 Mira Godard secured the representation of the estate of David Milne, who had died in 1953. Iconic today, Milne had been neglected by Canadian galleries since his death, with just three exhibitions mounted until Godard’s 1972 exhibition of paintings from the artist’s New York Period (1912-1922). Godard mounted regular exhibitions of his work thereafter, and succeeded in building interest in Milne’s work in major Canadian public galleries and private collections.

Another innovation of Godard’s was working with large and small Canadian corporations to build art collections. Before the mid-1970s many of those corporations was based in what was then Canada’s financial centre—Montréal. By the early 1970s, however, the political situation in Québec was prompting many corporations to move out of the city, a trickle that became a flood with the election of the Parti Québécois government in 1976. As early as 1971 Godard saw the writing on the wall, telling the Montreal Star that year that she did not “see a future, really, in Montreal, because to reverse momentum takes a long time.”[4]

Nonetheless, Godard strove to do just that. Her focus on bringing International art to Canada, and her connections with the New York art world, eventually led to her boldest move, a 50/50 partnership with one of the most powerful figures in the world of contemporary art: gallerist and collector Frank Lloyd. Lloyd’s Marlborough galleries were powerhouses in New York, London, Rome, and Zurich. In 1972 the Marlborough-Godard gallery opened in Toronto’s Yorkville, occupying the renovated townhouse in Hazelton Lanes where it remains to this day. Godard split her time between Toronto and Montréal (where the Godard-Lefort Gallery was also renamed Marlborough-Godard Gallery). The inaugural exhibition in Toronto featured mainstays of the Godard-Lefort days, such as Borduas, Gaucher, Lemieux, McEwen, and Christopher Pratt, as well as international stars from the school of Paris, the New York School, and from London, including Francis Bacon, Henry Moore, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Pablo Picasso. The rest of the season alternated between solo artists whom she represented, primarily Montreal artists, and international figures from the Marlborough galleries, including Alex Katz, Max Bill, Jacques Lipschitz, and Franz Kline.

Over the five years of her partnership with Marlborough, Godard mounted solo exhibitions by many prominent figures from their remarkable roster, including Mark Rothko, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, and Henry Moore. However, the gallery never lessened its focus on Canadian artists, with regular solo and group shows of artists from across the country, including Christopher Pratt, Jacques Hurtubise, Charles Gagnon, William Kurelek, and Gordon Smith, among many others.

The contract with Marlborough expired in 1977, and Godard renamed her gallery yet again, to the eponymous Mira Godard Gallery (Galerie Mira Godard in Montréal). The season in Montréal included the first solo exhibition at the gallery by Tom Forrestall. Also that year, Jeremy Smith and Ed Bartram joined the gallery, and have remained part of the Godard family of artists ever since. In 1978, Alex Colville had his first solo exhibition at Mira Godard, launching one of the most enduring partnerships in Canadian art.

In 1979, Mira Godard closed her gallery in Montréal, responding to the market realities of the day. It was not easy, she recalled, “because it was like getting rid of an old friend.”[5] That year Godard responded to the oil boom in Calgary by opening a Mira Godard Gallery there. The experiment was short-lived however, and the gallery closed in 1983 amidst a major recession. Godard decided that she could best serve her artists and clientele—who were based across the country—from one central location in Toronto, and that has been the gallery’s successful business model ever since.

Godard continued to be a major force in Canadian art for the remainder of her life, and she also took on an important philanthropic role. In 1988 she was named to the Order of Canada, the first art dealer to be so honoured. The citation noted that Godard was “a tireless advocate of Contemporary Canadian artists,” and that she “has been a major formative influence on the visual arts in Canada.”[6]

Mira Godard Gallery grew along with its artists. As young artists matured into established figures, she kept the market and the collectors engaged. While the gallery’s roster of represented artists changed over time, many of the best-known names in Canadian art have been represented by Godard for decades. Christopher Pratt had his first exhibition with Mira Godard in 1970, and Takeo Tanabe has been represented by the gallery for over 60 years. While active, the estate of Lawren S. Harris was entrusted to the gallery, and the estates of Alex Colville, Mary Pratt, and Jean McEwen, continue to entrust the legacies of these important artists with Mira Godard Gallery. She forged a relationship with the family of one the greatest Canadian Modernist painters that endures to this day— Mira Godard Gallery has represented the estate of David Milne for over forty-five years.

Generations of collectors have looked to Mira Godard Gallery for advice and inspiration, fuelling an interest in Canadian contemporary art that has served the art community for sixty years. In her lifetime Mira Godard was a tireless supporter of Canadian art and artists, a generous patron, and a valued voice in the diverse Canadian art scene. Since her death the gallery has continued under the distinguished direction of Gisella Giacalone, who worked with Mira Godard for many years.

Great commercial galleries survive because of trust. Mira Godard Gallery has survived for 60 years, a remarkable tenure for any institution. That Mira Godard Gallery not just survives, but thrives, is a testament to the enduring vision of Mira Godard herself, to the professionalism she embodied and inculcated into every aspect of her business, and to the strength of the relationships forged and fostered by the gallery that still bears her name.

[1] Agnès Lefort: Reflections of a Picture Seller (translated by Loa Lemire Tostevin), quoted in Lora Senechal Carney: Canadian Painters in a Modern World (Montreal and Kingston: McGill Queen’s University Press, 2017), p. 267.

[2] Quoted in Heather Dianne Fyfe: Mira Godard: Canada’s Art Dealer, MA Thesis for Concordia University, 2008, p. 27.

[3] Ibid., p. 30.

[4] Ibid., p. 36.

[5] Ibid., p. 37.

[6] Ibid., p. 66.

-

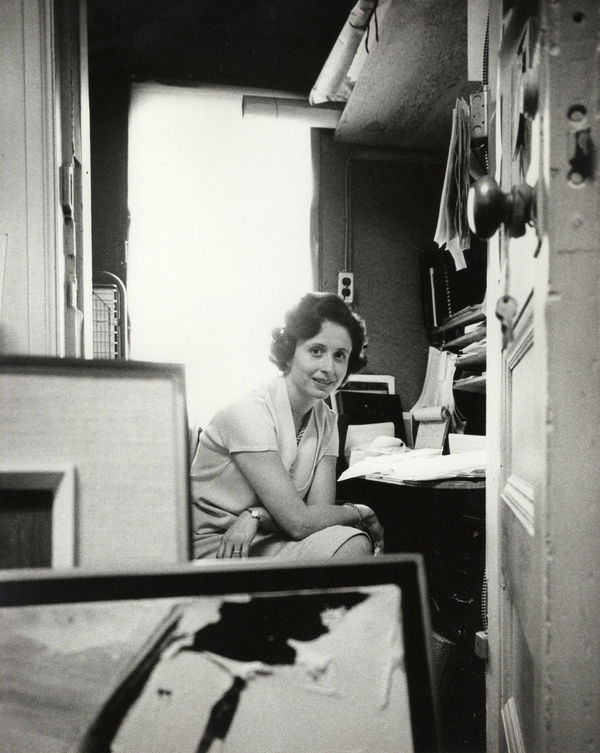

Phil Richards "Portrait of Gisella"

-

On Collecting

The Intimacy of Ownership — Essay by Dr. Eva Seidner“For a collector—and I mean a real collector, a collector as he ought to be—ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects.” In 1931 Walter Benjamin, while unpacking his books from the crates in which they had been confined for two years, paused to write a short philosophical “talk” on what he called “the bliss of the collector.” I came upon his essay “Unpacking my Library”in the basement of a now defunct second- hand bookshop on a drizzly November afternoon in 1983. As I read, I felt my own faint intimations of collector’s bliss stir and assert themselves. Benjamin, in speaking about the life and power of objects and his relationship to them, had revealed to me something I had not known about myself until that moment. I was by nature a collector, a “real collector,” to use his phrase.

The “bliss” to which he referred lay not only in the deliberate building of his collection but also in the fact that each object had come into his life at a particular place and time and often in a fortuitous way, all of which he vividly remembered. These attendant settings and events expanded the meaning of each book far beyond its textual content. The information contained between a book’s covers is available to everyone. But the accumulated nuances of a particular copy’s acquisition reside in the collector’s memory and are known only to him. It is these which make up the essence of a private book collection, distinguishing it from, say, a public library. “One thing should be noted,” Benjamin insisted. “The phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner.”

Not everyone considers such a personal “intimacy” of attachment to objects a defining characteristic of collecting practice. Regardless of your area of interest, as a collector you inevitably amass a collateral collection, a haphazard assemblage of anecdotes about other collectors. Two examples from my trove of Extreme Collector anecdotes, one from either end of the spectrum, will give you an idea of how widely divergent collecting styles can be.

Years ago, I fell in love with the work of Émile Gallé, the visionary Master of Nancy. For much of his career, Gallé worked in the Art Nouveau style, influenced by Nature and by japonisme, the European interest during the fin de siècle in the art of Japan. Between the 1880s and his death in 1904, his workshops produced high-quality furniture and decorative arts, graceful in design and meticulously executed. But around 1900 and until the year of his death, he created rare Symbolist works of art, sculptural glass objects of melancholy beauty and profound mystery. I sought them out in museums, pored over books and catalogues and listened intently to snippets of information scattered like confetti by auctioneers. In Paris I had the good fortune to be introduced to the author of a highly regarded book on the subject, illustrated with photographs of objects from his own collection. He invited a small group of visitors to his apartment the following afternoon. I was among them.

As expected, the apartment was filled with treasures, but I looked in vain for masterworks by Émile Gallé. When it seemed clear that the expert did not intend to show them to us, I asked if I might take a quick, discreet look. They were, after all, what I had come to see. He responded with a Gallic shrug.

“Pas possible,” he said, spreading his hands. “I did have some good pieces, but when I saw the ones I could never own, I sold my whole collection.”

For all I know, there may a Platonic purity in this kind of collection, a collection that is perfectly “complete” by virtue of its physical non-existence. Or perhaps the more desirable, unobtainable objects made the ones in the expert’s collection pale by comparison. His attachment to them broken, he no longer needed to own them.

The second anecdote involves a friendly looking man who suddenly appeared at my elbow in a booth at an art fair in Chicago. The gallerist had just affixed a red dot—my red dot—to the label of a large, dome-shaped sculpture of charcoal-grey cast glass. I stood gazing into its brooding depths, elated and spellbound, imagining this wonderful work of contemporary art in our home.

“Congratulations,” said the friendly looking man, whom I had never seen before. He held out his hand and announced his name in a tone that suggested that I should have already been familiar with it. “I collect Libenskys too, you know.” How many do you have?”

“One,” I said.

The proffered hand was instantly lowered. The man turned on his heel and walked away.

~

“Every collection,” says a character in one of Susan Sontag’s novels, “is always more than is necessary.” My passion for Émile Gallé and his turn- of- the- century world naturally made me curious about other members of the École de Nancy. Because I was infatuated and inexperienced, I bought too much. Our home began to fill up with furniture and objects by Gallé, Daum, Majorelle, Vallin, Gruber and others. I wanted not only to know but to feel. In retrospect I see that my early forays into collecting opened up intuitive capacities of which I had been previously unaware. Relying on my research skills and training as a literary critic, I had been preoccupied with thinking. What I craved was a deep sense of what it had been like to live among these objects when they were new.

Touch became an important part of this awakening need, especially with objects that could be held. Even more than sight, touch gave me intimate access to the past. My hands were touching an object that hands a century ago had touched and tended and kept secure. One day I heard an interview in which an archaeologist spoke of finding a fingerprint that a prehistoric potter had pressed into a clay vessel. “I fitted my finger into the exact spot where his finger had been,” the archaeologist said, “and I felt the connection, human to human, over a span of thousands of years.” Connection was precisely what I was seeking. By handling the objects in my collection, I came to “know” their essences. I experienced a kind of communion with the artists whose visions had given them life and the craftsmen whose skills had given them physical form. As my eye became more discerning, my fingertips acquired intuition and my imagination time travelled. One day, returning from an auction, I placed a small vessel next to another on a shelf, stepped back and experienced a surge of memories that were not—could not have been—my own. I felt that all these objects “knew” one another, had been together before and were content to be together again. I could almost visualize the high-ceilinged rooms in which they had resided, the people gathered together around the curved dining table in the orange glow from the cameo-glass chandelier I had just switched on. I had not deliberately collected these things in order to stage an “environment,” a calculated monument to the past. It was the aura of the gathered objects themselves which exuded the past, projecting it into the present. Even today, amid walls hung with contemporary paintings, the aura lives on.

I had my own memories of how and where each object had been acquired, but what I experienced during such moments in the presence of this collection felt much older and deeper. This was cultural memory, to which my European background resonated in sympathetic harmony. I had not grown up with these objects, yet I seemed to remember them or others like them. Had I simply acquired a taste for them, influenced by my parents’ descriptions of the lives they had led before coming to Canada, or was it the “lives” of the objects themselves I somehow felt drawn to? The lives of objects are their provenance, the documented history of their passage from hand to hand, owner to owner. Provenance is a fascinating subject, too large to open here, though I will return to it briefly later in the context of connoisseurship, of which it is a part.

Gallé’s late, Symbolist works became my transition from what is generally considered Decorative Art and Design, to Fine Art. I attended more painting exhibitions in public and commercial galleries and read more deeply in art history. My background in literary criticism adapted easily to looking at paintings and prints. The skills were almost identical: attention to detail and structure, rhythm and pattern, colour and atmosphere and nuance. Language, like the visual arts, is allusive and protean. The fewer preconceptions and the less ego you impose on the text or canvas, the more openly and freely it will communicate. As Jeanette Winterson sharply observed, “Art objects” to your impositions. A good viewer, like a good reader, sees the “white space,” the breathing space between the lines. Seeing is a creative act.

I deliberately avoided interpretation and over-thinking. What I was after, as before, was connection, the intimacy I experienced with objects, transposed to a medium still fairly new to me. Again, this drove my acquisitions. I wasn’t building a collection of any particular period or school, or even one in which the correspondences between paintings were obvious. I followed my instincts, trusting that they were increasingly informed by continuous looking and learning. I resisted consciously defining a through-line but kept to the notion that as long as the art I acquired was good, the collection would cohere. Meanwhile it grew, sometimes in unexpected directions.

One afternoon, attending an exhibition of Sudek photographs at the AGO, I was suddenly struck by the realization that not only must the art be good; the installation must be good as well. Sensitive installation choices create a context for a picture that expands a viewer’s appreciation and understanding, deepening his experience of seeing—even, ideally, inspiring him to return for another look, and another.

Here was another opportunity to explore the “intimacy of ownership.” I could experiment with how the collection was displayed in our home, could rotate objects in and out of display areas, much as public galleries do but on a much smaller, manageable scale. Though I never grew tired of anything in the collection, I found that moving things around renewed and enlivened them to my eyes. The communication among objects and paintings changed with reinstallation, especially when a new acquisition entered the “conversations” and necessitated creative reorganization. My experiments grew bolder. The less overtly “logical” and expected an installation, the more engaging its effect. I made a point of juxtaposing artworks made in different mediums and observed how the objects spoke to one another.

For instance, the patches of vivid, built-up colours in a cylindrical sculpture by the glass maestro Lino Tagliapietra come out of a different tradition from that of a Jean McEwen “Drapeaux inconnus” painting. But as abstract works of art that triumphantly employ opaque and translucent layers of colour, they show intriguing visual commonalties. Even more important to me is the similarity of their emotional impacts. “There are two ways to judge a painting,” said Jean McEwen. “One is based on criteria and theories of art. The second is based on sensations we get before a painting. I paint the second way.”

If all these adventures in looking, studying, acquiring and installing sound like play, it is because they are precisely that. But they are a transformative kind of play, not just fun but “bliss”—the “bliss of the collector,” to return to Walter Benjamin for a moment. Cultivated year by year, decade after decade, they grow into connoisseurship.

Another important aspect of connoisseurship is provenance, the tracing of documents that establish the passage of an art object from its creation through its history of successive owners, dealers, and public exhibitions, as well as its appearance in scholarly publications. Provenance plays an important role in establishing the authenticity of a work of art, the legality of a dealer’s right to sell it and a collector’s right to claim ownership of it. Fans of detective fiction will find engaging parallels in the many true accounts of provenance tracking: buried clues, tell-tale gaps in the evidence, and casts of characters ranging from the naive to the greedy to the outright sociopathic.

Like works of art, provenance can be forged, using fake documents or authentic ones nefariously “adjusted” or even stolen from public archives. If you’re tempted to go “down these mean streets” of provenance detection, one work among many I can recommend is Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art (A. Sujo and L. Salisbury, Penguin Books, 2009). Another is the documentary film The Art of Forgery (2014), about the flamboyant Wolfgang Beltracchi. He and his wife Helene succeeded in selling hundreds of his fakes, which she misrepresented to dealers and auction houses as originals inherited from her family’s collection. Many still hang undetected in museums and private collections. In 2011, Beltracchi and Helene were tried and convicted of selling fourteen such pictures and sent to prison. Asked if he had any regrets, he coolly replied, “Yes, I regret the titanium white.” He had accidentally used the pigment in a painting supposedly made by Heinrich Campendonk in 1914, when titanium white was not available.

While I continue to avidly follow provenance narratives, especially those relating to art restitution, for the past several years I have focused on collecting the work of living artists. I buy from well-established galleries with whom I have a sustained relationship, where I know my questions and concerns will be honestly addressed and where the act of acquisition is a transparent partnership among artist, gallerist and collector. There is an extra measure of joy in supporting the ongoing careers of artists whose vision challenges and enlightens me and whose dedication to the making of art inspires me.

Over the past months, as the pandemic has repeatedly surged and receded, I have been spending more than the usual amount of time at home. Being surrounded by art I love not only buoys up my spirits but also offers a surprisingly clear roadmap of my collecting life. I can see where it began, where it led me, where it veered off into side trips and blind alleys. It shows me where I am now and something of where I want to go next. Each work of art brings to mind memories of individuals, places, impressions, moods, weather, words spoken and left unspoken.

So intensely personal a relationship with objects entails a serious responsibility. Works of art can and should outlive the individuals who have them in their keeping. Collectors are less owners than stewards, tasked with maintaining artworks in the best condition possible and ensuring their safe passage into successive hands. Fanciful though it may seem, it is my hope that the bliss I experience daily in living with the works in my collection now also resides in the works themselves, to be transmitted to generations of collectors as yet unknown.